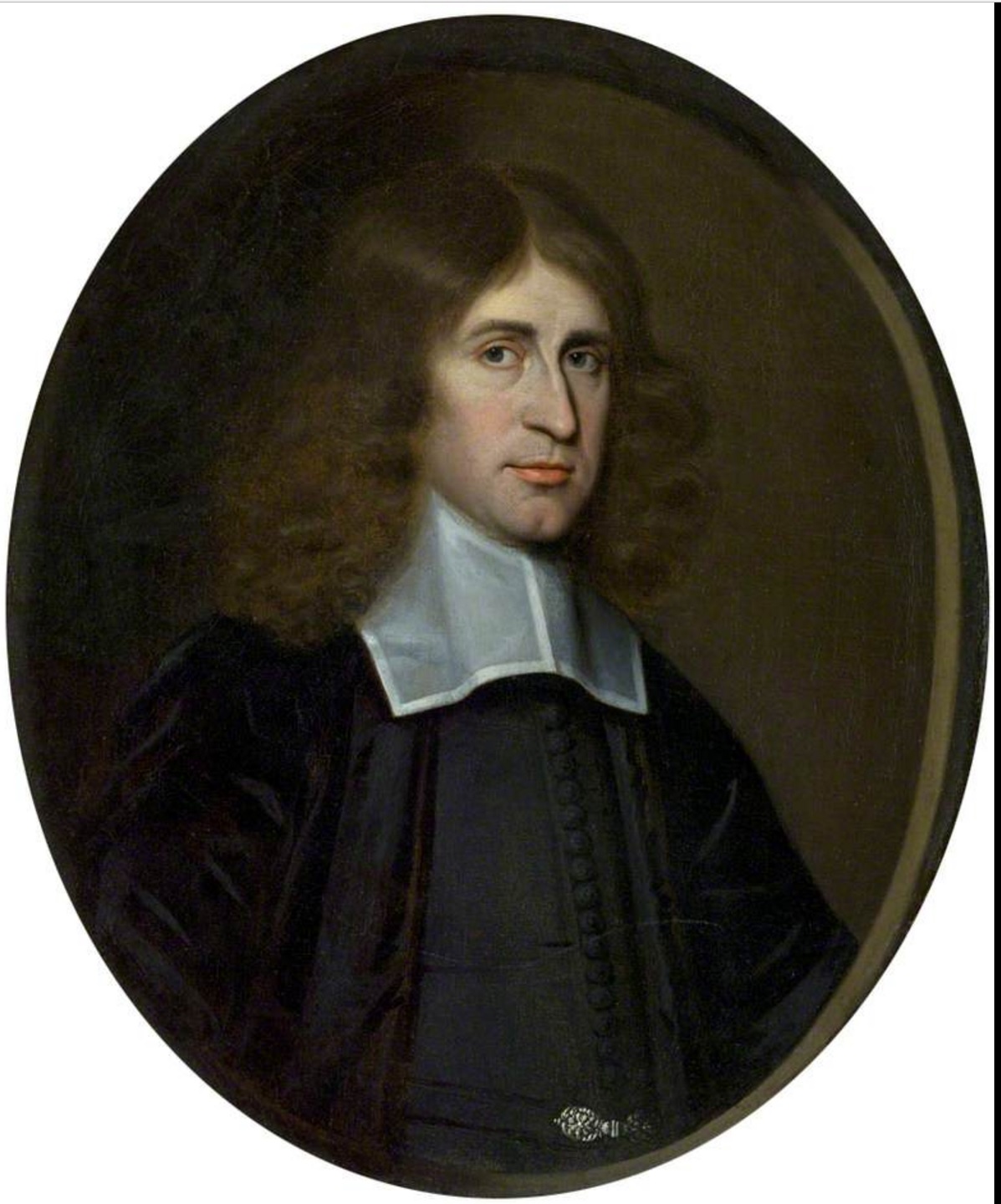

“whether a confederacy and association with wicked men, or such as are of another Religion, be lawfull, yea, or no” (chapter 14, A treatise of miscellany questions…)

His answer is…maybe. He rejected certain confederacies but allowed for others. Given that he is writing against a scholastic background (that I do not have) his use of Greek words and Latin were unclear to me.

After rejecting religious confederacies (naturally!), he next tackles civil unions:

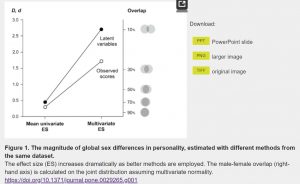

“But if the civill Covenant be such a Covenant as the Grecians called ![]() to joine in military expeditions together, of this is the greatest debate and controversie among Writers; for my part, I hold it unlawfull with divers good Writers…”

to joine in military expeditions together, of this is the greatest debate and controversie among Writers; for my part, I hold it unlawfull with divers good Writers…”

He continues to make arguments from the OT examples (but never explaining why the examples as such are binding). But his arguments are in the context of a society foreign to ours: the assumption that religion is integral and substantial in social and political life. In fact, they wanted Christianity explicitly part of the political union.

So the moral parallels with Israel become obvious. And his arguments have more force. But what would he do today when we have no such theological assumption nor ecclesiastical nor social unity to even push for some sort of Christian society?

But what would Gillespie do today? In his rejection of even civil confederacies with unbelievers he gives a clue:

“4. If we must avoid fellowship and conversation with the sons of Belial, (except where naturall bonds or the necessity of a calling tyeth us) Psal. 6. 8. Prov. 9. 6 and 24. 1. 2 Cor 6. 14, 15. and if we should account Gods enemies ourenemies, Psa. 139. 21. then how can we joyne with them, as confederates and associates, for by this means we shall have fellowship with them, and looke on them as friends.”

“Except where naturall bonds or the necessity of a calling tyeth us”–Natural bonds seems to mean family bonds (as he expounds later). Calling is the vocation or placement in life wherein God has placed us. We are not placed in Puritan England but in post-Christian America.

Thus we live in exceptional times.

In dealing with the counter-arguments to his position, his answer gives yet another clue (and brings more confusion to the reader):

“Those confederacies were civill, either for commerce, or for peace and mutuall security that they should not wrong one another, as that with Laban, Gen. 31. 52. and with Abimelech. Gen. 26. 29. which kinde of confederacy is not controverted.”

Interesting. Then my reading of “civil covenant” which he rejected is wrong. I do not know what he means by “civil covenant” (or confederacy as he seems to use it interchangeably). He clearly does not mean “commerce” or “peace and mutuall security.”

But in the American context that is closer to our political situation in the election year: who will we vote to maintain some “peace and mutuall security”–certainly not any Christian leaders since most of the government is not Christian.

A little later he gives a clue as to what he rejects in “civil covenants”: “so we ought to pray against and by all means avoide fellowship, familiaritie, Marriages, and military confederacies with known wicked persons, and such as are of a false or hereticall Religion.”

Again he states in a matter-of-fact fashion:

“There is again a conversing and companying with wicked persons, which naturall and civill bonds, or near rela∣tions, or our calling tyeth us unto, as between husband and wife, Parent and Child, Pastor and People, Magistrate and those of his charge. But wittingly & willingly to converse & have fellowship either with hereticall or prophane persons, whether it be out of love to them and delight in them, or for our owne interest or some worldly benefite this is cer∣tainly sinfull and inexcusable.”

“God forbade his people to make with the Canaanites foedus deditionis or subactionis, (or as others speak) pactum libe∣ratorium…”

There are those Latin words. I can translate them but I do not know their signification in his argument.

Later, he repeats the allowed exceptions to his position: ” The Law is also to be applyed against civill Covenants, not of peace, or of commerce, but of warre…”

Finally, he gives us an answer–maybe:

“I shall adde five distinctions which will take off all other ob∣jections that I have yet met with. 1. Distinguish between a confederacy, which is more discretive, and discriminative and a confederacy which is more unitive. And here is the Reason why Covenants of peace and commerce, even with infidels and wicked persons are allowed, yet military associa∣tions with such, disallowed: for the former keeps them, and us still divided as two: the latter unites us and them, as one, and imbodieth us together with them:”

It is unclear to me why a war covenant (NATO perhaps?) is more unitary than a commerce covenant.

But as much as he eschews civil covenants, he still allows one more exception:

“Neverthelesse, I can easily admit what Lavater judici∣ously observeth, upon Ezek. 16. 26, 27, 28, 29. that Cove∣nants made before true Religion did shine among a people, are not to be rashly broken; even as the beleeving husband, ought not to put away the unbeleiving wife, whom he married when himself also was an unbeleever, if she be willing still to abide with him. Whatsoever may be said for such Covenants, yet confederacies with enemies of true Religion, made after the light of Reformation, are altogether unexcusable.”

America may have socially and legally been Christian but politically (at the Federal level) we never were at the beginning.

This is the closest essay I can find relating to our unique situation today from the writings of our forefathers.

You can draw your own conclusions. Or you can read some of my researched conclusions here.