Rev. Greg Johnson shows that religious gay celibacy mostly fails; why does he think it will work today?

Greg Johnson, a gay PCA minister who has sworn celibacy, wrote a revealing book detailing how Evangelical efforts to assimilate homosexuals into their churches have failed. It may become the sort of classic that Marshall Kirk and Hunter Madsen’s 1989 After the Ball became among culture warriors.

Since America had not fully accepted gays, Kirk and Madsen declared the sexual revolution a failure. To remedy that, their book outlined a strategy for LGBT liberation by dressing up the carcass of the gay lifestyle with Madison Avenue techniques to normalize the sexual revolution.

Johnson’s work comes from the other side of that book’s narrative. He declares the anti-gay counseling efforts of the 1970s to be a failure. Those efforts were dubbed ex-gay: Christians renouncing their homosexual attractions, striving to be straight. Johnson disavows this approach yet tries to resurrect gay support ministries by urging Christians to restructure their church life for the benefit of LGBT people.

While Johnson makes the standard arguments that you hear from pro-gay religious leaders like Wesley Hill, he offers evidence and details hard to find anywhere else. That rare content is key to its importance, inadvertently illustrating the dangers of gay ministries.

Johnson insists that care should be the foundation of any gay outreach, one that keeps a steady eye on the world’s opinions. Thus, he demonstrates his effort to morph the ex-gay movement into a less-demanding call in the following: “The world is saying Christians hate gay people. Your children and grandchildren need to see you prove them wrong. The path forward is not a new sexual ethic. It is a new love.”

That “new love” is the well-trod rhetoric of the celibate gay (Side-B) crowd: stop the shaming, ignore the labeling and start giving gays free access to your fridge. The insistence upon love and acceptance permeates the book, while the law and the call to mortify attraction to the same sex takes a backseat.

His attachment to the LGBT community is so strong that he thinks our churches should lose members if anyone pushes back against the queering of the church. This affection for them is helpfully summarized in the story of Mark, a gay Christian who backslid with a “sexual encounter” at a bookstore. This sin brought so much guilt and despair on Mark that Johnson is prompted to write: “One wonders if there couldn’t have been room to breathe, room to fail.” Are promiscuous encounters at public places the kind of failure we should turn a blind eye toward?

However, when he pulls back part of the curtain of the sordid history of the ex-gay movement, the book’s instructional value becomes evident.

The failures of the ex-gay Christian ministries of the 1970s include the most obvious: the typical person involved in these groups did not change his orientation. Besides the negligent leadership and accountability failures, there was an ongoing effort to market their ministries. As one leader, McKrae Game of the group Hope for Wholeness, explained: “We in the ex-gay world are propagandists trying to propagate an ideal.” Then there are the porn addictions, suicides,and the astronomical divorce rate of gay men with straight women.

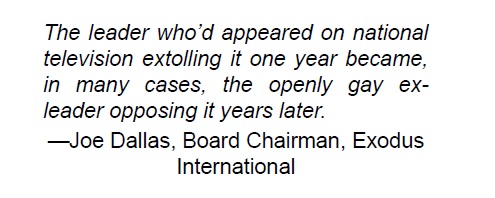

However, the more illuminating parts are the many shocking sexual scandals. We learn of the secret life of a homosexual minister who helped write the RPCES gay report of the early 80s. The leader in the ex-gay division of Focus on the Family was caught in a gay bar. Early on, an ex-gay leader of the most prominent organization (Exodus) came out with his partner, and both divorced their wives. And many speakers and leaders simply defected back to the homosexual life, as one ex-gay ministry chairman, Joe Dallas of Exodus International, admitted. There were also the sexual liaisons disguised as counseling sessions and male retreats that involved cuddling or group nakedness.

In his book, Johnson distances himself from the ex-gay movement, only highlighting their emphasis on curing gays, yet readers will likely see more similarities than differences. After all, both groups offer Christ, unconditional love, support, and espouse celibacy. Differences over self-identifying as gay (or not) feel more like debates over labels. All this brings readers to ask, “If many of the ex-gay ministries of the past were covers for active gay men, is that only a phenomenon of the past?”

Naturally, he blames the push to be heterosexual as the problem. Since they faced “incredible internal pressure” from donors and audiences alike to become straight, they failed. Johnson’s reasoning seems to imply the men were victims lacking moral agency and still does not ease the concerns that such pressures still exist.

To my surprise, he also dug into the history of non-straights in the Greco-Roman period. Again, Johnson delivers facts and quotes when other writers appear to avoid the uncomfortable topic. One description after another added together paints gays and bisexual men as sexually compulsive. He convincingly shows that the pederasty during the NT era included mutual sexual deviancy between the young and old. When a culture devolves, youth willingly yield to the groomers that surround them.

Even in the sections that are easy to disagree with, readers can find sparks of illumination. Such is the case where he writes at length how gays as a whole are “driven by [their] shame…” of being sexually aroused by men. Johnson acknowledges that such shame is not fundamentally “from homophobia, but it’s deeper than that.” Rightly, he explains that the shame “flows from being damaged by the fall” even as he deflects the moral implication of that.

Often, the fullness of his argument is unclear, leaving the reader to draw inferences or cobble things together from the book. For example, the implications of targeting this special interest group seem to leave the reader with an unhappy conclusion. If gay men refuse to leave the subculture while joining the church, they are heading for two outcomes: a messy exit or driving out the people who make the gay guy uncomfortable.

Johnson, who completed a Ph.D. in Historical Theology, also weakens his case with a barrage of emotional straight-bashing. Over and over, in strident tones, he warns against and accuses the church of “abuse.” Sounding like a variation of “words are violence,” he calls the church to repent, mirroring the pro-queer rhetoric that surrounds us.

Over all, given all the stories and historical facts, Johnson leaves his argument unfinished: If Johnson truly believes his paradigm is better than so-called (ex-gay) reparative therapy, how exactly will the scandalous sexual backsliding that he documents be prevented?

Yet Still Time to Care is an important work and teaches more than the author intended. Despite obvious theological and practical deficiencies (covered by other reviews), his book unwittingly reveals the cloudy future of the celibate gay movement. If pastors, elders, and laymen have time to care, they still have time to learn the right lessons from Johnson’s book.

(More in my forthcoming book, Is God Pro-Gay? Also, see my various essays on the growing celibate gay movement in traditional churches, see here).

thanks for writing the review and thanks for sharing.

Lue Anne

If the first order of business is to glorify God, then people like Greg Johnson would not waste their time focusing on their sin (Bible is clear), but focusing on God. I would add to that, that the Roman Catholic “priests” in large number, although all supposed to be celibate, are guilty of violating that celibacy and molesting children – the vast majority of which are homosexual molestations. The news media has covered this subject extensively. Greg Johnson to put it bluntly and crudely is urinating in the wind.